[Memorial Day Weekend] Fri, May 27 travel

Thunderstorms in Washington-New York corridor destabilize already-wobbly operation

Welcome to any new readers—we're grateful that you're here! We're building deep learning algorithms to democratize flight delay predictions; until we launch, we're eager to synthesize things manually in our outlooks. These feature several recurring themes that we recognize may be unfamiliar or intimidating, so we’ve written explainers that tackle airport arrival rates, queuing delays in the airspace and different tools to distribute those delays. If there’s a topic or mechanism you’d like to see unpacked, please let us know (same goes for special travel occasions).

Last weekend was kinda a letdown, huh? Headed into Thursday, the trend in our TSA throughput forecast was angled quite steeply upward—more so than any point in the preceding four weeks. We estimated there was a 3 in 4 chance to break the single-day pandemic record for travelers screened. Then each of the next four days came in at the lower end of our forecast, including Friday’s 31st percentile performance. So are we getting our hopes up again for a record-breaking weekend? You best believe it.

Our Holt-Winters model assesses a 42% probability for Friday to exceed 2.45 million screened, the current high-water mark (belonging to the Sunday after Thanksgiving 2021). However that model doesn’t “see” the holiday, so we feel it understates the chances: Some back-of-the-napkin forecasting using 2019 patterns suggests it’s more like 50/50.

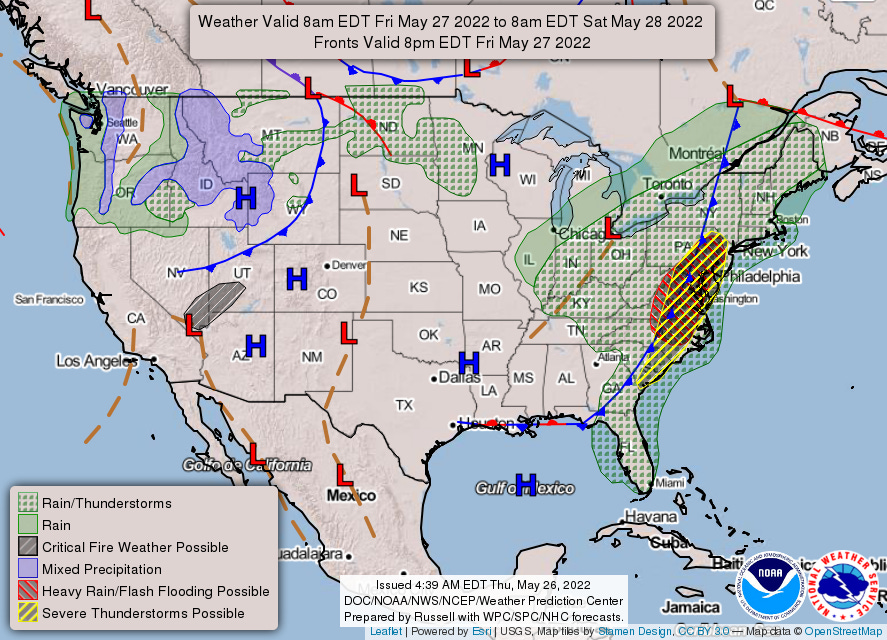

If tomorrow does break a record, travelers will have earned their participation badge—a wrapped up storm system is set to swing its cold front across the central Appalachians, snarling air traffic along the East Coast. Airlines need this additional strain like they need a circular runway1, with Delta having told employees they’ll be proactively thinning this weekend’s schedule to alleviate pressure on operating groups. As of 4 p.m. ET Thursday, Delta has cancelled 63 mainline flights tomorrow (2% of schedule).

Southeast

Let’s get started in Charlotte (CLT), where the frontal boundary looks to exit the area by late morning, but not before American Airlines’ second-largest hub operation is well underway. Fortunately, we think 72 is a reasonable arrival rate floor (less than 1 in 10 chance for equal or lower rates) and morning scheduled arrival demand2 peaks at 59 (in the 10 a.m. hour). In the absence of a demand overage, we don’t anticipate air traffic delays at CLT tomorrow; of course delays owing to aircraft servicing, airline staffing, network effects, etc. are always lurking. We’ll also highlight the risk for a ramp closure—all it takes is one ill-placed lightning strike to pull baggage handlers, fuelers and mechanics inside, thus halting aircraft turnarounds. Both caveats—generic staffing/servicing delays as well as ramp closure-related disruptions—apply to the other geographies we’ll consider.

We took a peak at Atlanta (ATL), however thunder chances taper off pre-dawn and ceilings are forecast to lift by 8 a.m. Before we move on from the Southeast, we also will mention potential impacts to Florida airspace (i.e. ZJX and ZMA). The cold front is forecast to cross the Panhandle early Friday morning, reach the north/central Peninsula later in the day then stall over central/southern Florida. The forecast discussion from the Melbourne NWS office indicates sea breezes should be a more than serviceable ignitor for numerous thunderstorms, but models depict rather sparse convective coverage. We don’t like to bet against NWS meteorologists, but conviction about their solution doesn’t make prognosticating about resulting air traffic delays any more viable. As we wrote in our last Spring Break outlook:

Historical data on airspace—rather than airport—capacities is buried a bit deeper (we’re digging), so it’s difficult to put even rough probabilities around capacity tomorrow. That said… more modest constraints can be expected to reduce capacity by approximately 15-25%.

For the moment, including the possibility for an airspace flow program (if thunderstorm coverage is more dense than models currently depict) is the extent of our capabilities.

Mid-Atlantic

Showers and thunderstorms—some on the strong to severe side—could develop over the Shenandoah Valley by mid-morning then translate eastward by afternoon. A moist, southerly flow will promote back-building of thunderstorms during the evening as well as training. We think there’s at least a 1 in 8 chance for arrival rates in the range of 26-28 at Washington-Reagan (DCA), where scheduled demand peaks at 33 (in the 9 p.m. hour). While there’s little question that convection pressures airport capacity in the afternoon and evening, there’s some uncertainty as to whether ceilings by themselves can do the same in the morning (forecast as low as 800’). We assumed DCA opens up at a 28 rate then steps down to 26 at 5 p.m., which produces 19 minute3 average delays across the day. Respite during the late morning depresses the average intensity, however, and delays exceed 25 minutes in all but one hour from 2 p.m. to 11 p.m.; delays crest at 51 minutes in the 9 p.m. hour.

Whereas demand at DCA is relatively uniform, Washington-Dulles (IAD) features 4 banks—between banks, scheduled arrival demand is typically less than 10 flights. The first two banks should sneak in ahead of the convection’s arrival; the largest bank operates during the late afternoon, including 54 scheduled arrivals during the 4 p.m. hour. Here we don’t anticipate it will be a matter of rate-setting as much as wait-and-see. While we think there’s a better than 2 in 5 chance for an arrival rate between 62-64, we don’t think total demand (i.e. scheduled and unscheduled4) will challenge capacity. Instead, we’ll be watching to see if thunderstorms shutoff arrivals to produce airborne holding and possibly a ground stop. The dynamic figures to be nearly identical for bank #4 during the late evening.

Gulf moisture should surge at least as far north as Philadelphia (PHL), though the frontal boundary loses some definition. Despite some synoptic differences, the forecast is shaped similarly to Washington airports, including at least a marginal severe threat. We like 32 for a low-end, albeit not improbable, arrival rate: We’d put chances at around 2 in 5 for an equal rate (though less than 1 in 20 for lower rates). Scheduled arrival demand peaks at 57 (in the 5 p.m. hour), with 3 other hours at or above 34 scheduled arrivals. We modeled an all-day 32 rate, wherein delays briefly spike to around 25 minutes during the 9 a.m. hour, lay down for the remainder of the morning, then are stoked again during the early afternoon (max delay during noon hour is 31 minutes). The most extensive disruption occurs during early evening, when delays exceed 45 minutes during the 5 and 6 p.m. hours.

New York City

Much of the day should remain dry for the NYC metro area before a broken line of showers and thunderstorms approaches from the west during late afternoon and evening. Some training is possible here as well. Similar to DCA, there’s a question as to whether drizzle will pressure airport capacity during the morning (ceilings forecast at 400’ and visibility down to 1 mile) separately from thunderstorms during the evening. For Newark (EWR), we’d put chances at 1 in 4 for arrival rates less than or equal to 29 and at least 1 in 2 for rates less than or equal to 32. We think EWR should realize a 36 arrival rate during the midday period—let’s say from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Otherwise, we’ll assume EWR opens up at a 32 arrival rate and wraps up at a 29 rate. While resulting delays are minimal through the 2 p.m. hour (6 minute average), delays from 3 p.m. average 50 minutes. Delays exceed 90 minutes in the 9 and 10 p.m. hours and the operation slides into the 1 a.m. hour.

Across the river at New York-LaGuardia (LGA), we’ll set up an arrival rate floor at 26 (1 in 10 chance for equal or lower rates); our chair rail, so to speak, is constructed at 34 (2 in 5 chance for equal or lower rates). Similar to EWR, we modeled some midday improvement (36 arrival rate from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m.), with moderately constrained capacity (34 arrival rate) on the front end and the lowest rates (26) on the back end. Delays through the afternoon are modeled to be manageable (less than 20 minutes), though quickly ramp up around 6 p.m. and for the last 6 hours of the day average 54 minutes. Delays reach a peak of 86 minutes in the 10 p.m. hour.

Finally, for New York-Kennedy (JFK), we think there’s a 1 in 5 chance for arrival rates less than or equal to 32 and an incremental 1 in 10 chance for arrival rates between 34-36. Here we modeled a 36 arrival rate through the 10 a.m. hour, 8 hours at a 40 rate, then closing out at a 32 arrival rate. Like EWR, delays through early afternoon are nearly negligible (4 minute average through 1 p.m. hour), then turn upwards—though not the almost 10x increase experienced at structurally disadvantaged EWR. Delays peak at 39 minutes in the 11 p.m. hour, though the operation concludes shortly after midnight.

Recommendations

American, Delta and JetBlue have issued weather waivers and we’d expect United to follow suit. There figures to be ample cause to take advantage of the flexibility these afford (though optionality remains to be seen). Specifically, if you’re scheduled to connect via DCA, EWR, JFK, LGA or PHL during the late afternoon or evening and your layover cannot absorb a delay of at least 45 minutes, we’d encourage you to check alternate itineraries. While not delay free, morning and midday layovers at these airports look to be a safer bet.

Which is to say not at all, contrary to Mashable’s suggestions.

Cargo airlines as well as private jets are not included in scheduled demand and only become apparent when they file a flight plan (generally day-of). This unforeseen demand introduces the risk that delay probabilities/intensities are under-forecast. From April 25 to May 24, unscheduled demand has added 14.0% to scheduled demand for Core 30 airports. For the airports we’ll consider in this post, only IAD (44.1%) and PHL (20.8%) are above-average by this measure.

While our modeling is aimed at tackling arrival delays, there's a strong correlation to departure delays (albeit with some lag and/or possible alleviation). Consider a scheduled "turn" at an airport: the inbound flight is scheduled to arrive at 2:19 p.m. and departs at 3:30 p.m. (71 minutes of turnaround time). Let's say the inbound is delayed by 40 minutes and instead arrives at 2:59 p.m. We'll further assume that the airline doesn't need the full 71 scheduled minutes to turn the aircraft and can accomplish the turn in 45 minutes if they hustle - the departure will push back from the gate at 3:44 p.m. (delayed by 14 minutes). In this example, a 40 minute arrival delay in the 2 p.m. hour is partially passed through to a departure in the 3 p.m. hour. Had the turnaround been scheduled at 45 minutes instead (i.e. no turnaround buffer), the lag between arrival and departure delay would still exist, however the delay would be fully passed through.

While IAD has more unscheduled demand than most (see footnote 2), since Mar 1, scheduled and unscheduled demand coalesced to reach at least 62 flights during the 4 p.m. hour just 3.5% of the time.

For months the DL C-Suite has insisted that they’d run the summer schedule at 100%. This was tough enough to pull off pre-COVID. I don’t know anyone that thought it would actually happen, but there they were over and over trying to will it all into existence. I’m leery of any kind of regression in flight count, but in this case it makes sense.