Holiday cancels through the lens of geography and utilization

We know this is at least the third such review published this week, but we think we've found some unexplored corners of the topic

No boilerplate needed about explainers for this one, though we still want to welcome new readers—we’re grateful you’re here!

Instead, we’ll use this space to solicit suggestions: with the holiday travel season having wrapped up, we’re on the lookout for future travel occasions we can cover. Please drop any suggestions in the comments (we’re quite happy to write about more localized events).

As Brett Snyder at Cranky Flier and David Slotnick at The Points Guy have already nicely summarized the cancellations that roiled airlines for the last two weeks, we wanted to find a different angle from which to examine the disruption. Given that our burgeoning reader base is either pretty curious or technical as best as we can tell, we decided to steer into some deeper waters. While the drivers we’ll discuss may not be readily apparent, we think by the end of this post you might agree that they were among the most influential variables.

Geography

Winter weather certainly contributed to disruption, with Seattle probably at the top of that list1. Cranky and TPG both attributed—rightfully so—some cancellations to these colder, wetter geographies, so we’ll refrain from discussing snow removal and deicing. Instead, we’ll consider the shape of the Omicron surge and how it overlapped with various carriers’ networks.

As Omicron first exploded in the Northeast, some carriers would be disadvantaged by their geographic concentration while others were afforded a [temporary] degree of protection. We elected to consider the distribution of block hours2, rather than departures or seats, because it more accurately captures where pilots and flight attendants—the most constrained populations—are deployed.

It helps to explain why JetBlue’s (B6) deterioration was as steep as depicted in the above-linked articles (their cancellation rate climbed to 12% in the first 3 days). And perhaps United’s (UA) narrow “lead” in the Northeast over Delta (DL) was the reason United was at the forefront of cancels on December 23 (and therefore first to find themselves in the headlines). Regrettably, we weren’t able to wrangle cancellation data for GoJet (G7) or Republic (YX); GoJet would have been easy to overlook—they’re the smallest carrier by departing seats that we considered—but we can’t help but wonder if Republic was an unheard canary in the coal mine. Where block is distributed also offers an explanation as to why some carriers were seemingly able to stave off cancellations, Southwest (WN) probably chief among them. As we’ll see in a moment, though, Southwest was operating on a knife’s edge.

Pilot Utilization

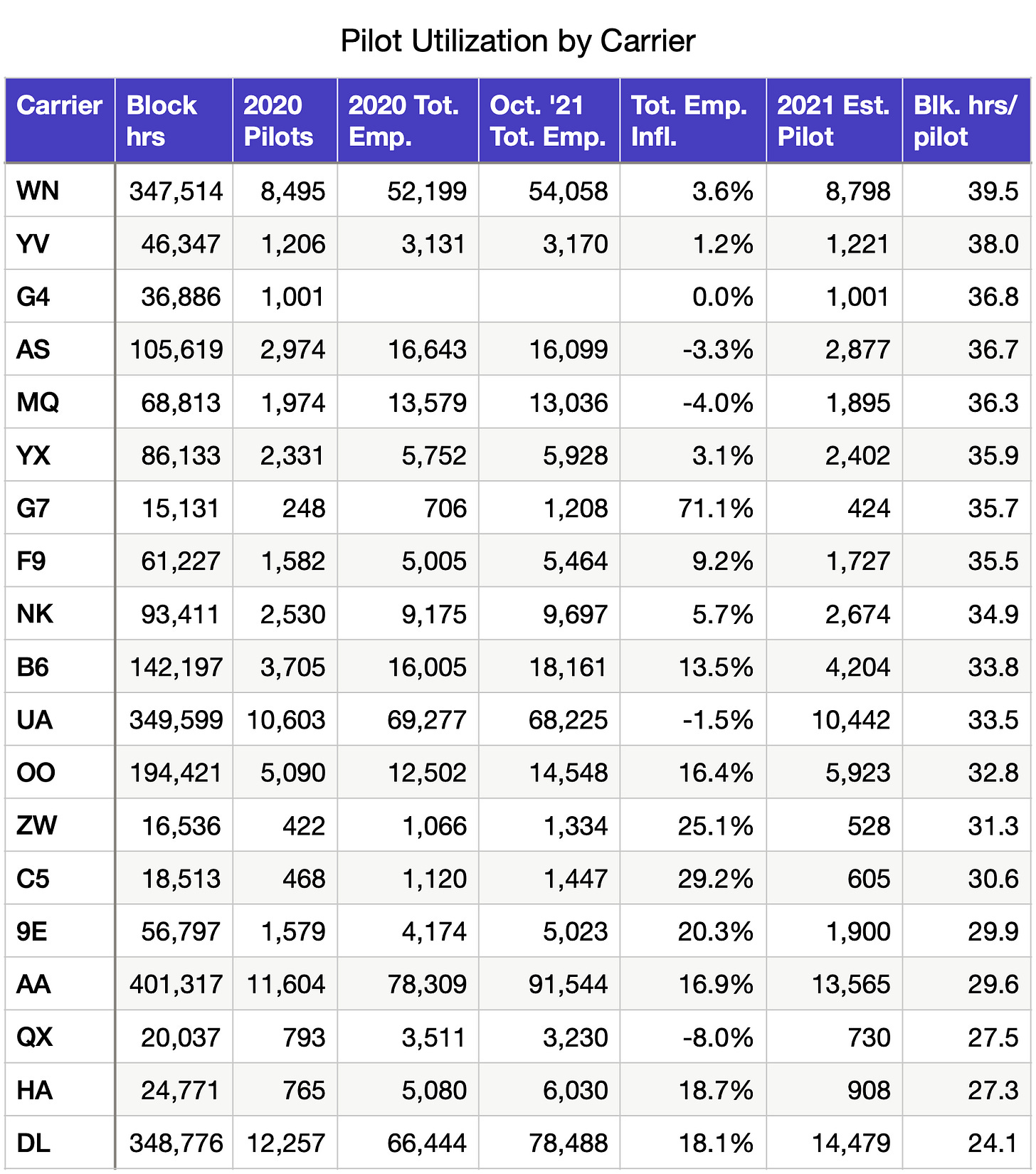

While there’s an element of luck or randomness in Omicron’s track (and weather, for that matter), our second variable is a calculated decision by airlines. We’ve attempted to reproduce the results of these decisions in the table below: we estimated the number of hours that each pilot is counted on to fly (i.e. utilization). Put another way, it reveals how much risk each pilot represents in the event of a sick call. Block hours were readily available from OAG selling schedules, however estimating the pilot population was a bit trickier. The most recent airline employment data (Oct. 20213) does not differentiate by employee group, so we adjusted 2020 pilot populations4 by each carriers’ change in overall employment between the two snapshots. In most cases, this represented inflation, as the weighted average from 2020 reflected something near the bottom. On account of collective bargaining restrictions and training lead times, applying overall employment change to pilot groups is an imperfect assumption, but we think worthwhile on the balance.

When considering how highly leveraged their pilots are, it’s hardly a surprise that Southwest (WN) has assumed the unenviable position atop cancellation laggardboards (per FlightAware, they cancelled 658 flights, or 21% of their operation, yesterday). This data also inclines us to believe that Alaska (AS), who cancelled the highest percentage (14%) of their schedule over the holiday period, would have struggled even absent winter operations in SEA. Evidently AS leadership agreed, as they announced yesterday that they’d reduce departures by about 10% through the end of January. Oppositely, it instills some appreciation for Delta’s relatively conservative scheduling approach. And it might answer how American (AA) was able to avoid headlines for the most part—by some combination of luck and strategy, they managed to protect both flanks.

When considering how highly leveraged their pilots are, it’s hardly a surprise that Southwest (WN) has assumed the unenviable position atop cancellation laggardboards

While a bit cluttered, we also wanted to share a neat bit of data visualization (in our opinion) that shows how carriers are arranged across both dimensions. We plotted each carrier at an average5 latitude/longitude and sized the bubble according to pilot utilization.

Post-Holiday Passenger Demand

The last factor we’ll mention is declining passenger volumes. We approximated load factor by considering travelers screened by TSA as a percentage of seats departing US airports: while Omicron no doubt precipitated6 the decline, this is a pattern that typically kicks off the Tuesday after New Year’s Day.

Our measure of load factor has fallen on each of the last 4 days, reaching 54.8% on Thursday. Softer passenger volumes bias an airline towards the cancel button, as fewer customers will be interrupted and more seats will be available to rebook those disrupted travelers. While light bookings by themselves are unlikely to beget cancels, when operational constraints force airlines into a defensive posture, low load factors may net a few more cancels on the margins.

Geographical advantages and disadvantages seem likely to wash out as Omicron ebbs and flows. We expect pilot utilization, on the other hand, will prevail to order cancellation laggardboards—for this reason, we’ll be keeping a close eye on weekly updates to selling schedules. We’re betting this weekend’s update removes January block hours for a couple carriers and we’ll be back with updated pilot utilization estimates.

SEA’s 9.2” of snow already exceeds the average of 6.6” during the last 10 seasons; it’s also the snowiest December since 2008. DEN, CHI and WAS were other notable airports/metros that dealt with winter weather.

By departing station. Block time is the duration scheduled to elapse between pushing back from the origin gate (“blocking out”) to setting the brake at the destination gate (“blocking in”).

Schedule P-1(a) Employees from DOT BTS contains the monthly interim operations report of full-time and part-time air carrier employment for major, national, large regional, and medium regional air carriers.

Schedule P-10 from DOT BTS provides annual employee statistics by labor category.

Weighted by departing block hours.

We couldn’t get through a blog without the use of precipitate, even if in a different form than normal.