[Spring Break] Friday Apr. 8 travel

Snow to mix with rain at Chicago O'Hare, plain rain forecast for Seattle. And what happed last Saturday??

Welcome to any new readers—we're grateful that you're here! We're building deep learning algorithms to democratize flight delay predictions; until we launch, we're eager to synthesize things manually in our outlooks. These feature several recurring themes that we recognize may be unfamiliar or intimidating, so we’ve written explainers that tackle airport arrival rates, queuing delays in the airspace and different tools to distribute those delays. If there’s a topic or mechanism you’d like to see unpacked, please let us know (same goes for special travel occasions).

Welp. We picked the wrong weekend to stop sniffing glue to focus on some data science work. When we were writing our post last Tuesday, NOAA’s Weather Prediction Center had identified the frontal boundary that would stall over Florida during the weekend; however, they expected “scattered to widespread showers” to accompany the front. Unfortunately, scattered showers would evolve (devolve?) into a line of strong to severe thunderstorms that parked themselves over central Florida. Friday would require a state-wide ground stop to manage. (Even the Command Center seemed to know that they’d need to affirm that yes, they mean the entire state.)

While Friday was challenging—albeit not anomalous with respect to the scale of delay—Saturday was untenable. An airspace flow program (or APF, which is like a ground delay program for a parcel of airspace) spanning Jacksonville Center was published with rates as low as 80: the normal rate is 250. Average delays of 308 minutes resulted. Moreover, route closures on the eastern (via the Atlantic) and western (via the Gulf) boundary of the AFP severely limited airlines’ ability to route out of the problem. If these en-route initiatives slowed operations to a trickle, then 4+ hour ground stops virtually halted Florida air traffic. Nearly 2,000 flights were cancelled on Saturday, followed on by 1,500 cancellations on Sunday as airlines attempted to get back on track; for some airlines, recovery lingered into Tuesday.

So we’re not particularly proud of our prognosticating as it relates to last weekend’s disruption. But it appears we made a better call about the direction of traveler volumes. After drifting downwards for two weeks, it looks like the 7-day moving average of TSA throughput found a floor on Sunday, settling at 2.049 million travelers. While Monday’s initial bounce didn’t exactly inspire confidence (increasing the smoothed average by just 5 basis points), Tuesday and Wednesday both inflated the 7-day moving average by more than half a percent. With 8 of the 20 largest municipal school districts starting their Spring Break this weekend, we have no reason to believe this upward trend will lose momentum. Our Holt-Winters forecast likes 2.32 million screened on Friday, which would be good for second highest in the last 30 days1; some back-of-the-napkin math using 2019 patterns points to 2.38 million screened on Friday, which would rank first in the last 30 days.

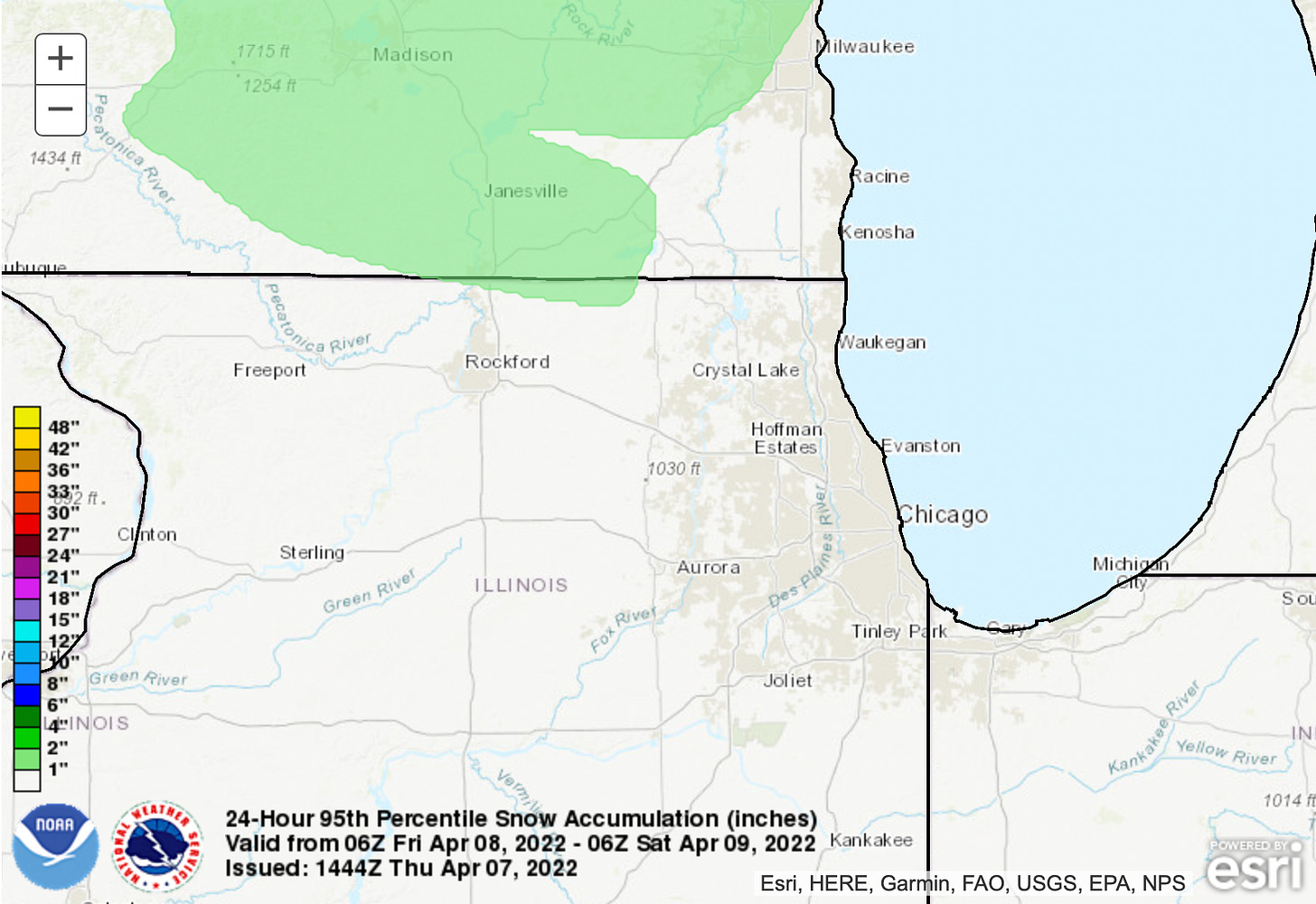

What’s in store for these travelers on Friday? As low pressure2 slides across the Great Lakes, abnormally cold air is pulled down from Canada, allowing snow to mix with rain for the Upper Midwest. Meanwhile, the next Pacific cold front brings rain to the Pacific Northwest tonight into Friday morning.

Chicago O’Hare (ORD)

The forecast discussion from NWS Chicago doesn’t rule out some all-snow showers or patchy, slushy accumulations. This largely agrees with the outlook from the Weather Prediction Center (another NOAA outfit), which keeps accumulations below 1” even at the 95th percentile. Rain/snow showers look to persist into Friday night. While that level of accumulation should not pressure airport capacity, ceilings and visibilities may be enough to drop arrival rates. We’re inclined towards the TAF3, which keeps visibilities at 4 miles; the National Blend of Models (NBM) drops visibilities to 2 miles for most of the day. We think there’s a 1 in 4 chance for arrival rates between 86-88.

The good news is when scheduled arrival demand4 peaks at 99 in the 7 a.m. hour, weather is not yet forecast to have deteriorated. The bad news is the second tallest peak is 91 in the 6 p.m. hour, firmly in the window for lowered ceilings/visibilities. If an 88 arrival rate is realized for the 6 and 7 p.m. hours, we’ve modeled approximately 1,800 minutes of delay that would need to be distributed. There’s some question as to how these delays would be administered. We’re confident the FAA will take a wait-and-see approach, so we can take a ground delay program off the table. There will be more support for the use of metering or miles-in-trail to resolve the overage if relatively little unscheduled demand is introduced to the equation [therefore not exacerbating the imbalance]. In this scenario, delays would be indiscriminately allocated and are not modeled to exceed 20 minutes5. Otherwise, the FAA would be left to reach for a first tier ground stop, which disproportionately distributes delay to those arrivals originating within 700 miles or so. In the case of a first tier ground stop, delays for captured flights average 16 minutes.

Additionally, departure delays for deicing should be expected if snow is falling. (And, of course, delays owing to aircraft servicing, airline staffing, network effects, etc. are always lurking.) As an aside, we wondered if this would be the last time we’d be writing about snow at ORD this season, but climate normals suggest not. The timing is about right for the last measurable snowfall (i.e. at least 0.1” of snow), which—on average—falls on April 2. But the last trace snowfall averages April 14 (and has occurred as late as May 25). Moreover, the 14-day forecasts strongly favors below-normal temperatures (and near normal moisture).

Seattle (SEA)

The frontal system will reach the Washington coast by this evening, with rain spreading inland overnight. Wet conditions are forecast to last throughout Friday. A southerly wind develops this evening with the switch to the onshore flow. Scheduled arrival demand equals 45 in the 10 a.m. hour: we estimate there’s a 3 in 10 chance that capacity will be sufficient. At the lower end of the range, we’d set SEA’s arrival rate floor at 40 (1 in 10 chance to occur). Like ORD, the use of metering or miles-in-trail is marginal at the lower end of arrival rates; if viable, delays are not modeled to exceed 20 minutes, given a 40 arrival rate. Conversely, a first tier ground stop in the 10 a.m. hour would produce average delays of 31 minutes for captured flights.

The NMB suggests ceilings scatter out around 8 p.m., when 48 arrivals are scheduled. If the NBM verifies in this respect, we think there’s a 6 in 10 chance that capacity will be sufficient; if conditions do not improve, we think there’s only a 1 in 10 chance for adequate capacity. We’ve modeled a 40 arrival rate and resulting first tier ground stop: delays average 40 minutes and linger into the 9 p.m. hour.

Recommendations

Though no weather waivers have been issued that cover Friday travel, we will take the opportunity to remind readers that airlines have meaningfully improved general rebooking flexibility by eliminating change fees for most tickets (though a fare difference may still apply). We’ve linked to the same-day change policies for Delta (who operates a SEA hub) as well as American and United (ORD). There are a couple connecting itineraries that would prompt us to consider alternatives:

the trip starts in the Pacific Northwest, Intermountain West or Northern California and includes a layover at SEA around 11 a.m. or 9 p.m. that cannot absorb a delay of at least 30-40 minutes;

or the trip starts in the Great Lakes or Plains and includes a layover at ORD around 7 p.m. that cannot absorb a delay of at least 20 minutes.

The other [broad] category of connecting itinerary we’d keep an eye on originates within the Upper Great Lakes (e.g. Traverse City or Green Bay) and—to a lesser extent—the Upper Mississippi Valley. Lake-effect snow will likely result in intermittent deicing delays for departures from this region. Regardless of where the layover is scheduled, the tightest connections could be broken by the deicing delay to the inbound flight. In these cases (and in general), reach out and we’re happy to provide a more specific forecast!

The Holt-Winters model gives Friday a 18% chance to set a new pandemic high-water mark, which is currently 2.45 million and belongs to the Sunday after Thanksgiving 2021.

The National Weather Service has a great online weather school called Jetstream and we’ve linked to its synoptic meteorology topic. In a sentence, high pressure generally promotes fair weather while clouds and precipitation are associated with low pressure.

Terminal aerodrome forecast (TAF) is a format for reporting weather forecast information, particularly as it relates to aviation. TAFs are issued at least four times a day, every six hours, for major civil airfields: 0000, 0600, 1200 and 1800 UTC, and generally apply to a 24- or 30-hour period, and an area within approximately five statute miles from the center of an airport runway complex.

TAFs complement and use similar encoding to METAR reports. They are produced by a human forecaster based on the ground. TAFs can be more accurate than Numerical Weather Forecasts, since they take into account local, small-scale, geographic effects. Source: Wikipedia

Cargo airlines as well as private jets are not included in scheduled demand and only become apparent when they file a flight plan (generally day-of). This unforeseen demand introduces the risk that delay probabilities/intensities are under-forecast. Since Mar. 1, unscheduled demand has added 14.6% to scheduled demand for Core 30 airports. For the ORD and SEA, unscheduled demand adds 7.2% and 4.9% respectively.

While our modeling is aimed at tackling arrival delays, there's a strong correlation to departure delays (albeit with some lag and/or possible alleviation). Consider a scheduled "turn" at an airport: the inbound flight is scheduled to arrive at 2:19 p.m. and departs at 3:30 p.m. (71 minutes of turnaround time). Let's say the inbound is delayed by 40 minutes and instead arrives at 2:59 p.m. We'll further assume that the airline doesn't need the full 71 scheduled minutes to turn the aircraft and can accomplish the turn in 45 minutes if they hustle - the departure will push back from the gate at 3:44 p.m. (delayed by 14 minutes). In this example, a 40 minute arrival delay in the 2 p.m. hour is partially passed through to a departure in the 3 p.m. hour. Had the turnaround been scheduled at 45 minutes instead (i.e. no turnaround buffer), the lag between arrival and departure delay would still exist, however the delay would be fully passed through.