An alternative method for estimating pilot populations

Why we believe regional airlines are short more than 2,500 pilots; plus, aircraft utilization as a proxy for airline health and some insight on Frontier-Spirit

Last week’s SkyWest earnings release was the latest exhibit submitted in the case of Regional Pilot Shortage vs. U.S. Airlines. In it, SkyWest disclosed:

“Given recent staffing challenges, we currently anticipate block hours in 2022 may be down approximately 10%-15% from our 2021 production.”

We had previously approximated pilot populations as part of our pilot utilization analysis; that first estimation relied on the DOT’s airline employment tables1. Given the gravity of the problem, we think an alternative methodology is warranted. Let’s walk through how we approached this second approximation then we’ll compare results and merits.

How did we calculate how many pilots they have?

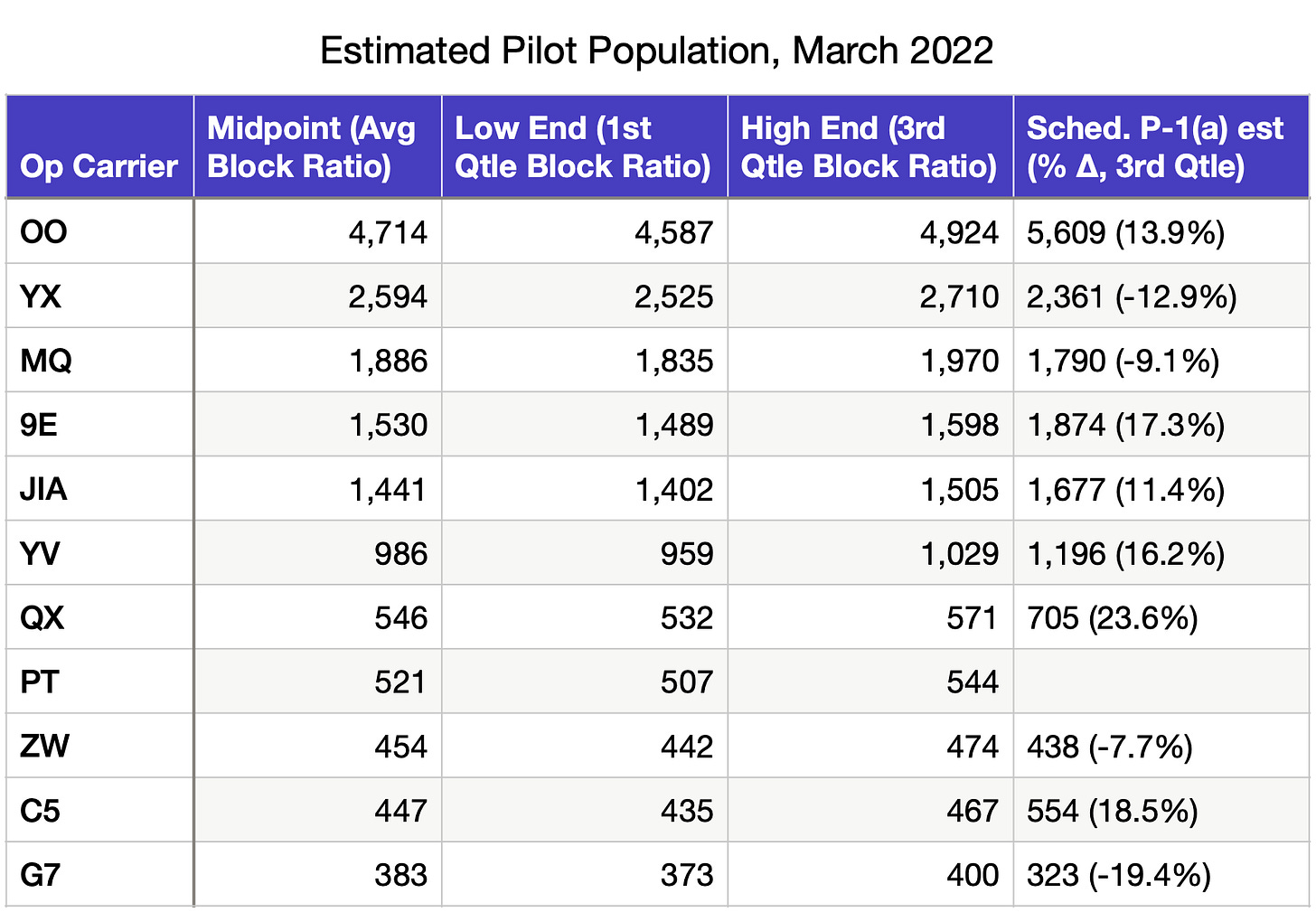

We’ll start with two familiar variables: pilots and block hours. Rather than assume pilots are independent from block hours and can be unlimitedly leveraged, we’ll essentially index pilots to block hours. During a relatively normal 2019—when demand for and supply of pilots was closer to equilibrium—reporting regional carriers2 employed approximately 1.31 pilots for every daily block hour. While we’re now assuming pilots vary with block hours, multiple carriers do provide a range of values, with a first quartile of 1.28 pilots/block hour and third quartile of 1.37. Let’s apply these 2019 pilot per block ratios to March 2022 scheduled block time (from OAG), assuming that airlines will have sized block hours according to pilot availability.

We also included our estimates derived from the first methodology, i.e. adjusting 2020 annual population by monthly trends from Schedule P-1(a). In many cases, this comes in above the upper end of our second methodology, suggesting our first approach understates the severity of the problem. Our second approach to estimating pilot populations has the benefit of removing much of the reporting lag (even interim monthly reports were a month or two stale, to say nothing of the 2020 starting point), which is important in an environment that’s apparently rapidly deteriorating.

As we covered in last week’s review, Current Schedules teams were rather busy cutting first quarter schedules during January. While these reductions were generally attributed to Omicron, an unequal distribution of cuts across regional carriers hints at a more structural problem coming to a head. Between the Jan. 3 and Feb. 7 OAG snapshot, the aggregate March block reduction for regional carriers was 8.3%. For PSA and SkyWest, reductions approached 12%; for Mesa, reductions equaled 21.8%. Meanwhile, carriers like Republic (0.5% reduction) held up considerably better. From where we’re sitting, it looks like the floor is falling out from underneath some carriers—and the nearness3 of cuts implies some difficulty in wrapping their arms around the problem.

How does this compare to what’s needed?

This second methodology also lends itself to understanding how many pilots an airline “needs” and, in turn, measuring the depth of the shortage. Here we’ll start with an industry rule of thumb: for every aircraft on property, an airline should employ 14 pilots. This number is more reflective of mainline carriers, however, and their longer stage length inflates the ratio. Thankfully, the DOT furnishes the data4 necessary to calculate this number for individual operating carriers. For reporting regional carriers5, the ratio was more like 10.7 pilots per aircraft during 2019; once again, that multiple carriers report provides a range of values (first quartile is 9.7 and third quartile is 11.7). Let’s apply these 2019 pilot/aircraft ratios to current fleet sizes to estimate how many pilots regional airlines would require to fly their airline at “normal” levels. Additionally, we’ll bring in our above pilot population estimates to approximate the difference between needed and available.

Aircraft are even less fungible than pilot populations, with fleet plans made years in advance, and it’s conceivable airlines will have accepted additional aircraft despite a shrinking pilot population. SkyWest’s quote at the top of this post seems to corroborate our midpoint estimate: we estimate that they’re 735 pilots, or 13.5%, short of a full complement. Their disclosure also suggests SkyWest (OO) is representative of the aggregate regional airline industry, which we estimate has a shortfall of more than 2,500 pilots (14.1%). As we’ve already hinted at, not all regionals are positioned equally and, alarmingly—even in a best case scenario— we estimate Mesa (YV), Air Wisconsin (ZW), CommutAir (C5) and GoJet (G7) are short pilots by at least a quarter, if not more than a third.

What are the implications?

One downside to the alternate methodology is some difficulty in making comparisons between carriers. We’re hesitant to divide block time by an estimation of pilot population derived from the same block time to recalculate pilot utilization. Fortunately [for the sake of this exercise—unfortunately for the state of the industry], we can use a different type of utilization: aircraft utilization. In a normal environment, aircraft utilization is bound by time-of-day traveler demand patterns and the scheduling constraints we outlined in the above-linked review of first quarter reductions. For 2019, aircraft utilization (daily block hours per aircraft) for regional carriers equaled 8.36. In 2022, it appears the limiter on aircraft utilization is pilot availability, with airplanes being idled for lack of pilots. Using the same current fleet counts from our second table and March scheduled block time from the first table, we calculated March aircraft utilization; the vertical axis is sorted by total block time, with largest (SkyWest) on top.

We think this measure more intuitively scales the problem (for as long as pilot availability is the limiter), highlighting the same concerns as earlier—YV, ZW, C5 and G7—while dispensing with the percentage comparison. We find is curious (maybe a little suspicious) that two carriers wholly-owned by American (MQ, JIA) appear to be best positioned, especially when other wholly-owned subsidiaries (9E, QX) are in the middle of the pack. For those carriers that don’t have a mainline parent, the stakes are uncomfortably high. Regional airlines provide flying to mainline carriers under “capacity purchase agreements,” wherein the mainline partners pay a rate that varies with the number of completed flights, flight time and the number of aircraft under contract. As block hours are reduced to accommodate the pilot shortage, regional airlines revenues are also dragged down. Unfortunately, costs associated with non-pilot labor, maintenance facilities and flight operations support are not as elastic. Notably, aircraft costs were not included in that list of inelastic costs—the mainline partner typically compensates the regional for the costs of owning or leasing the aircraft. Nevertheless, it’s conceivable that the regional carrier would also be responsible for aircraft lease or debt commitments in cases where the aircraft is removed from service due to pilot unavailability7.

Whether somebody runs out of pilots or runs out of money, we probably wouldn’t take a bet that all 11 regional carriers we’ve considered survive in the same form (looking at you, ExpressJet). Even for non-wholly owned subsidiaries, mainline has some interest in propping them up, at least in the near-term: some diminished capacity is better than no capacity at all. Over the longer term, however, it would be more efficient for the same, if too small, pool of regional pilots to be spread among fewer carriers.

Bear Fare? (We wish we could take credit for that quip)

The Frontier-Spirit merger announced yesterday morning has understandably garnered the majority of aviation attention so far this week (though The Air Current’s deep dive on the Boeing-FAA relationship shouldn’t be overlooked). Initial reverberations of the merger have already been well-covered (including articles from Simple Flying and The Points Guy as well as a blog post by Seth Miller), so we won't spill too much more virtual ink on the topic. That said, we think it notable—and believe we were first to uncover this—that the merged carrier is set to become the second largest in Florida. They’ll jump Southwest and Delta, remaining behind only American (with a hub in Miami). We took a quick cut at seat share in the merged carrier’s top 10 airports; the horizontal axis is sorted by combined March 2022 seats, with largest (Orlando) at left.

We also found it interesting that the 14 pilots per aircraft mentioned earlier founds its way into the Frontier-Spirit discussion:

In the merged airline’s case, many of these new hires figure to matriculate from regional carriers… the industry certainly does not lack thematic entanglement.

We’ll be back later this week with a look at Super Bowl inbound travel!

The most recent airline employment data (Nov. 2021, from Schedule P-1(a) Employees) does not differentiate by employee group, so we adjusted 2020 pilot populations (from Schedule P-10) by each carriers’ change in overall employment between the two snapshots. In most cases, this represented inflation, as the weighted average from 2020 reflected something near the bottom.

9E, MQ, OH, OO, YV, YX

Had the depth of pilot attrition been forecasted, then base versions of the March schedule—likely under construction around a November timeframe—would have been built to an appropriate level of flying. While there’s some optimistic bias in the early stages of schedule building (i.e. from Futures), that drastic schedule reductions were implemented after day-of-week changes suggests to us that training inductions missed expectations or more pilots left for mainline than predicted.

Schedule B-43 Inventory

9E, G7, MQ, OH, OO, QX, YV, YX

For 9E, MQ, OH, OO, YV, YX. Our Network readers may think this is low: we’re calculating fleet utilization, rather than in-schedule utilization (i.e. fleet less spare, maintenance, etc. allocations).

Mesa Air Group 2019 Annual Report, pg. 7, “During the temporary removal…”