Selling schedule updates: Jan. 8 edition

United reduces remaining January schedule by nearly 4%; plus some insight on selling schedules, what counts as a cancel, block shaving, types of fruit and CASM.

As expected, airlines gave their close-in selling schedules a haircut this weekend, with almost 6,500 fewer flights planned to operate in January than this time last week. That’s a lot of Ctrl + x1.

No boilerplate needed about explainers for this one, though we still want to welcome new readers—we’re grateful you’re here!

Instead, we’ll use this space to solicit suggestions: with the holiday travel season having wrapped up, we’re on the lookout for future travel occasions we can cover. Please drop any suggestions in the comments (we’re quite happy to write about more localized events).

Before we dive in, a quick lesson on how airlines manage their selling schedules. Flights are bookable approximately 330 days in advance, however beyond 90-120 days, schedules would traditionally bear only a loose resemblance to what the airline actually planned to operate. When air travel demand cratered in the first quarter of 2020, that horizon contracted to more like 30 days; as demand has stabilized, airlines’ Network Planning teams have fought hard to push that threshold back out. Importantly, selling schedules are generally updated once per week: though this update begins late Friday night, given its size, processing is not completed until early Saturday (and depending on what system one is using, may not be accessible until late Sunday). Somewhere around 7-10 days from departure, Network Planning transitions responsibility for the flight schedule to operating teams, at which point schedule changes are no longer bound by a once weekly cadence. It’s also only inside of 7 days from departure that a flight is considered cancelled as far as the DOT is concerned—while a few of the closest-in flights that came out this weekend might count as a cancel, for the most part, these won’t show up in FlightAware, etc.

What got cut?

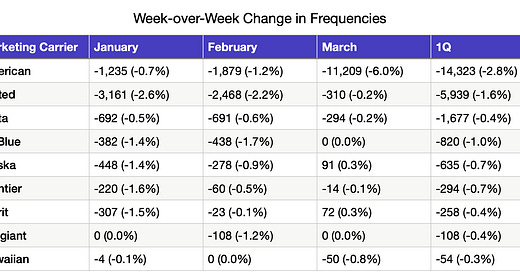

Let’s consider changes at the marketing carrier-level2 before recalculating our operating carrier pilot utilizations. We looked at reductions across the first quarter, by which measure American ranks first. However, the bulk of American’s reductions were focused on March—as we touched on above, it’s difficult to know whether this was a product of their planned timeline (as they work to return to pre-COVID horizons) or in response to Omicron. Regardless of American’s reason, we think the most interesting story is over at United, who was decidedly most aggressive with their January schedule.

United’s reductions are more impressive when considering they start on the 12th of the month: while their cuts equaled 2.6% of the calendar January schedule, they’re equal to 4% of the post-Jan. 11 schedule. Unsurprisingly, United was most prejudiced towards their Boeing 737 fleet, which seems to have been afflicted with the highest incidence of pilot sick calls. Reductions in B737 flying totaled 3.8% of calendar January flying, whereas cuts to other Mainline fleets were just under 2%. Geographically, Cleveland (CLE), Fort Meyers (RSW) and Fort Lauderdale (FLL) all lost at least 10,000 departing seats in January (between 8-11% of capacity); a handful of smaller stations also lost at least 20% of their capacity (CPR, SLP, GJT, HRL, ONT, MFE).

Needless to say, eliminating flights is critical for reducing block time3. But it’s also important what flights the airlines pick on—cutting a JFK-LAX will remove a lot more block than LGA-BOS. To this end, the average distance, or stage length, for United’s reductions was 1,163 miles (approximately as long as Chicago O’Hare to Miami). We’d say that’s reasonably efficient in terms of how much block each cut removes. Delta’s Mainline flying was untouched by reductions, yielding a relatively inefficient average stage length of 724 miles for cut flights. Oppositely, Alaska and JetBlue were most efficient in this respect, with average stage length for reductions equaling 1,471 and 1,337 miles, respectively.

We also suspected we might see some block shaving, wherein airlines would merely trim a minute or two off of flights. Whether the airlines intend to fly faster (by increasing fuel burn), anticipates shorter taxi times or accepts lower reliability, it’s tough to envision such a tactic contributing to a solution in this case. Thankfully, we found little evidence of this: block per mile for January decreased in this weekend’s update by about half of one percent at CommutAir (C5, a United regional partner) and even that’s marginally attributable to block shaving (more likely owes to shifts in geographical mix). Otherwise, block per mile decreases were less than one quarter of one percent in this weekend’s update (and February as well as March actually show some signs of block buffering).

How did the cuts impact pilot utilization?

Alright—so we have a grasp on how many flights airlines removed and how efficient those cuts were. We’ll transition to an operating carrier view, as pilots fly not for the brand but operator, and recalculate pilot utilization (i.e. the amount of hours each pilot is counted on to fly). As Brett Snyder of Cranky Flier rightly pointed out in our Twitter exchange, pilot utilization comparisons between carriers may not be an apples-to-apples comparison: fleet commonality, base counts, stage length, and bargained incentive pay can all influence outcomes. But we still think it’s at least an apples-to-pears4 comparison and a worthwhile exercise to roughly understand how highly pilots are leveraged.

Readers may notice differences in estimated utilizations derived from the Jan. 3 snapshot owing to both the numerator and denominator. The DOT has since released November 2021 airline employment data since our Friday post; we’ve also decided to “inflate5” 2020 pilot populations using full-time employee numbers, rather than full-time equivalent (we think this better captures the “stickiness” of pilot collective bargaining agreements and training). Lastly, we narrowed our focus to January (i.e. block hours from Dec. 16-31 are no longer included), as this post is more forward-looking (we also stopped short of including February because modeling suggests Omicron will have meaningfully receded by then6).

GoJet (G7) assumes the spot atop our revised pilot utilizations, suggesting a relatively high level of operational risk associated with each pilot sick call. GoJet’s ascent is mostly attributable to the revised pilot inflation methodology—they still receive the largest upwards adjustment in pilots (30%), however it’s smaller than the previous method (71%). Southwest (WN) remains the highest among their Mainline peers, having not removed any block time in this weekend’s update. On the other hand, utilization most substantially relaxed week-over-week at CommutAir (C5, who flies under the United brand) and Mesa (YV, who flies under the American and United brands), which should benefit travelers. And some breathing room looks to be badly needed at both CommutAir and Mesa, having cancelled an industry-worst 20% of yesterday’s schedules per FlightAware. Given that crews have already been assigned their January schedule (i.e. the month is already “bid”), it’s tough to say how many of these block hours the airline will be able to recoup. At a minimum, however, that these flights were removed from travelers itineraries further in advance should beget better outcomes by way of longer rebooking lead times.

At a minimum, however, that these flights were removed from travelers itineraries further in advance should beget better outcomes by way of longer rebooking lead times.

We’ll close out today’s post with some speculation for any financially-inclined readers. These block reductions also pull out ASM’s, which will pressure CASM7. We won’t hazard a guess on the impact to expenses—as alluded to above, there’s considerable sunk crew cost associated with January reductions. Coupled with overtime being exhausted at airports (i.e. gate agents and baggage handlers), piling trip interruption costs and netting out fuel expense… we’ll leave that to some investment analyst. But if one assumes expenses (excluding fuel) will equal 3Q21, then this weekend’s ASM reductions represent, most notably, a 0.94% and 1.25% increase in 1Q22 CASM for JetBlue and United, respectively. We wouldn’t be surprised to see updated financial guidance from some airlines once they digest the impacts themselves.

And that’s a joke for a very narrow demographic.

American, Delta, United and Alaska operate their own flights, considered their Mainline operation (on larger jets, with upwards of 100 seats). These airlines also “purchase capacity” from regional carriers (e.g. SkyWest), wherein the regional carrier operates smaller aircraft (i.e. less than 100 seats) under the Mainline brand.

Block time is the duration scheduled to elapse between pushing back from the origin gate (“blocking out”) to setting the brake at the destination gate (“blocking in”).

In botany, apples and pears are both examples of pomes. A pome is a type of fruit produced by flowering plants in the subtribe Malinae of the family Rosaceae. Source: Wikipedia.

Bet you didn’t think you’d be reading about fruit morphology when you opened this post.

The most recent airline employment data (Nov. 2021, from Schedule P-1(a) Employees) does not differentiate by employee group, so we adjusted 2020 pilot populations (from Schedule P-10) by each carriers’ change in overall employment between the two snapshots. In most cases, this represented inflation, as the weighted average from 2020 reflected something near the bottom.

Cost per available seat mile is a measure of unit cost in the airline industry. CASM is calculated by taking all of an airline’s operating expenses and dividing it by the total number of available seat miles (ASM) produced. Sometimes, fuel or transport-related expenses are withheld from CASM calculations to better isolate and directly compare operating expenses. Source: MIT Airline Data Project

Excellent work Tim. Keep these very well done analyses coming.