Disruption at Newark Airport (EWR), oft-featured in our air travel outlooks, has been spotlighted after comments from United CEO Scott Kirby during the company’s first quarter earnings release. Kirby (straining to remain calm by his own account) responded to a question about capacity and demand at the airport by saying:

It’s outrageous what's being allowed to happen at Newark. The airport has the theoretical capacity to fly 79 operations per hour. That's what the FAA says. That's in perfect conditions, which are rare at Newark. It was the most delayed airport in the country in 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019. And the FAA has rules that limit the airport to 79 operations per hour, and they are letting airlines violate those rules.

That Scott did not reach further back into the 2010s was hardly an effort to keep his answer concise—in 2015, Newark ranked third-highest in terms of arrival EDCT incidence1. So what changed in 2016?

How we got here

On April 1, 2016 (in what some2 initially thought was a very uncharacteristic April Fool’s joke), the FAA announced that EWR would transition from a Level 3 to Level 2 airport. The new designation meant that EWR would no longer be slot-coordinated, but schedule facilitated; practically, it required that the FAA seek voluntary schedule adjustments from airlines to alleviate delays. The order originally designating EWR as a Level 33 took effect in 2008 and pointed to concerns about spillover effects from New York-Kennedy (JFK). The 2008 order was allowed to expire on October 29, 2016 pursuant to the April 1 announcement, in which the FAA referenced improved EWR operational metrics while also alluding to planned 2017 runway construction at JFK.

The effects of the transition to a Level 2 designation were apparent almost immediately. In the following 90 days, 24.8% of arrivals to EWR were assigned an EDCT, nearly doubling from 12.8% during the same period the year prior. For their part, nearby—and still slotted—New York-LaGuardia (LGA) and JFK were up 5.5 percentage points (to 19%) and down 0.2 percentage points (to 4.8%), respectively. This pattern would broadly continue through 2019, with 26.8% of EWR arrivals assigned an EDCT4—ceding 5.3 percentage points in EDCT incidence to LGA and 19.2 percentage points to JFK.

With the onset of COVID, the FAA announced a slot usage waiver on March 16, 2020 that applied to Level 3 and 2 airports5; the waiver would be thrice extended, availing relief through October 30, 2021. Thereafter, its scope was pared back6 to waive usage requirements for international operations only. Resultantly, frequencies at EWR, JFK and LGA, which were languishing at 69% of 2019 levels in October 2021, quickly bounced to 93.1% in November. With flight schedules trending towards more normal levels—and the demand for airports’ runways that they represent—delays have responded in kind. From October 31, 2021 to April, 26, 2022, 9.7% of arrivals to EWR were assigned an EDCT, up from less than 1% during the same period the year prior. And EWR has again assumed its spot as laggard, giving up more than a percentage point of EDCT incidence to LGA and 8.7 percentage points to JFK.

What is this theoretical capacity Scott mentions?

In the quote at the top of the post, Scott referenced 79 operations per hour, which may sound suspiciously similar to the arrival rates we love to write about in our disruption outlooks. Crucially, 79 is intended to capture the omni-directional capacity (both landings and takeoffs), not just arrival capacity; it also reflects a planned capacity bounding (supposedly) airline schedulers months-ahead, not a rate tactically called by air traffic controllers day-of. While there’s some room to shift capacity between arrival and departures on the upside (more on that later), capacity is less malleable to the downside. With dedicated arrival (4R/22L) and departure runways (4L/22R), it’s quite conceivable that excess capacity exists on EWR’s departure runway at the same time that the airport is short landing slots. Unfortunately, EWR is unable to use both runways concurrently for arrivals: the idle departure capacity is unused and a queue results for landings.

On account of this intractability, we’ll halve (and round up) the 79 operations per hour to get a 40 landings per hour cap. How does that compare to realized arrival capacity? Since October 31, 20217, arrival rates have been less than 40 during 29.6% of hours—and that’s during the generally more benign, less convective half of the year. Let’s tack on the other half of the year, though we’ll look back to April-October of 2018, when runway rehabilitations caused less distortion. Across all seasons, actual EWR arrival rates were less than the planned 40 landings per hour in 31.4% of hours. Meanwhile, 71 operations per hour are authorized at LGA, conveying a limit of 36 landings per hour; actual arrival rates were less than 36 in 24.2% of hours. Capacity is more malleable at JFK, where 81 operations are authorized per hour. For the sake of comparison, let’s go ahead and halve/round up while keeping in mind that they enjoy more flexibility: actual JFK arrival rates were less than 41 in just 12.7% of hours.

Putting it together with the demand side

So even if EWR is able to deliver an arrival rate analogous to its approved cap (scarcely a safe bet), the question is not the frequency at which scheduled operations exceed 79 but scheduled arrivals exceed 40. Since October 31, 20218, scheduled arrivals have exceeded 40 in 10.6% of hours. Across the river, scheduled arrivals at JFK and LGA have exceeded their implied landing caps (41 for JFK, 36 for LGA) in 4.3% and 5.8% of hours respectively. There’s also the matter of unscheduled demand, i.e. cargo airlines and private aircraft that do not file schedules with the likes of Cirium or OAG. At EWR, unscheduled flights have added 2.5% on top of scheduled demand9; though comparable to JFK (3.0%), actual arrivals have come in underneath schedule arrivals at LGA (suggesting scheduled cancellations have outpaced unscheduled adds).

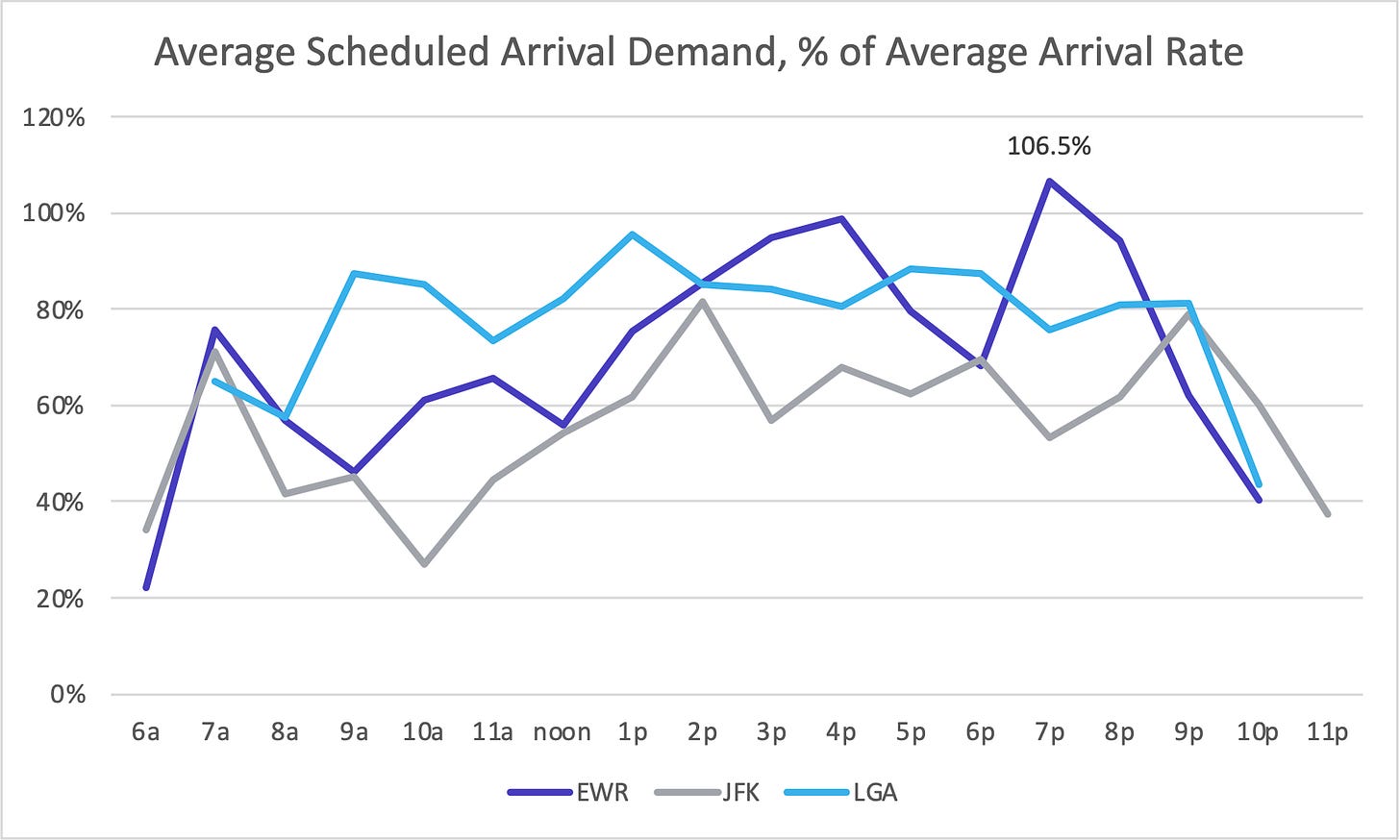

These capacity and demand disadvantages are especially combustible during late day, when delay is arguably built-in: on average, scheduled arrival demand (41.1 flights) exceeds capacity (38.6 arrival rate) in the 7 p.m. hour. In zero hours is this the case at JFK or LGA, where average capacity utilization peaks at 81.7% and 95.7%, respectively. And while the 7 p.m. hour is an apt microcosm of the problem, EWR struggles to find capacity-demand equilibrium for much of the afternoon and evening. From 3 p.m. through the 9 p.m. hour, scheduled arrival demand equals 86.4% of capacity, on average. For the same period, average capacity utilization at JFK and LGA is 64.4% and 82.6%, respectively. Delays unfold accordingly, with 17.7% of EWR arrivals in that 7-hour window assigned an EDCT since October 31, 2021—more than 6 percentage points higher than LGA and 16 percentage points higher than JFK.

It’s gonna get better, right?

Er. Let’s again consider capacity and demand separately, as improvements to either side of the equation could at least alleviate the problem.

The most obvious buoy to capacity would be another runway, which is an almost laughable request in most cases. But EWR is a unique case. We had highlighted Runways 4R/22L and 4L/22R above, though intentionally excluded Runway 11/29 due to its under-utilization. Runway 11/29 is used less than 15% of the time, which is a shame because it unlocks the airport’s ability to handle an additional 8 arrivals per hour. The reasons for this under-utilization could fill their own post; for now we’ll note its short (but not too-short) length, potential conflicts with Teterboro (TEB) traffic and prevailing wind direction. Otherwise, the ability to use both primary runways for arrivals concurrently—whether arrivals are sideby or staggered—could unlock an additional 6 arrivals per hour. A 2014 FAA capacity profile suggested requisite procedures would be available by 2020, but no such configuration has popped up in the data yet. Perhaps a reader in the know can clue us in.

While we’re apathetic about the capacity outlook, we’re more concerned about the direction of demand. Controlling for days in the month, July 2022 flight schedules (which we believe reflect airline intentions at this point) are set to grow by 9.3% versus April 2022. Moreover, regulatory influences look to further stimulate demand, as the DOT is set to award 16 additional operations during the afternoon and evening peak10.

As long as regulators are in an approving mood, perhaps they’ll increase JFK’s authorized hourly operations by 6 to 87—at that cap, they can still be expected to deliver equal or better arrival rates with more success11 than EWR or LGA. We’re not holding our breath, but such a move could rebalance demand within the aggregate New York City market.

Among Core 30 airports. An estimated departure clearance time (EDCT; commonly referred to as a wheels up time) is assigned to flights inbound to an airport when demand for the arrival airport’s runway(s) exceeds its capacity. EDCTs hold (read: delay) flights on the ground at their origin airports. Source: FAA ASPM

You can read more about airport capacity, how excess demand creates queueing and various traffic management initiatives in our explainers.

Me, who spent considerable time slotting United’s day-of-week schedules.

73 FR 29550 (May 21, 2008)

For the period Jan. 1, 2017 to Dec. 31, 2019

85 FR 15018. In the case of Level 2 airports, the waiver prioritized flights canceled for purposes of establishing a carrier's operational baseline in the next corresponding season.

Document ID FAA-2020-0862-0344, COVID-19 Related Relief Concerning Operations at… for the Winter 2021/2022 Scheduling Season

Through Apr. 24, 2022; reportable hours only.

Through Apr. 24, 2022; reportable hours only.

For reportable hours, Oct. 31, 2021 to Apr. 24, 2022.

Document ID DOT-OST-2021-0103-0040

Actual JFK arrival rates were less than 44 in 19.5% of reportable hours for the period 4/25/18-10/30/18 and 10/31/21-4/24/22.

https://www.flightglobal.com/united-wants-dual-approaches-at-newark-to-expand-hub/123214.article

https://www.faa.gov/airports/planning_capacity/profiles/media/EWR-Airport-Capacity-Profile-2014.pdf